If you’re looking for a legal, mind-bending way to spend 6 minutes and 30 seconds, check out Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream, from 1965’s Bringing it All Back Home. If you’ve got a bit more time, say, 95 minutes, take a peek at Alex Cox’s 1987 film Walker. Or if you’re just drowning in time, say, I dunno, probably a good 10 hours (or do I just read slow?), William T. Vollmann’s 1994 novel, The Rifles.

I suppose you could read, watch, and listen to all three at the same time. Maybe they were even designed that way.

One thing these three pieces of art have in common is that they are pretty eccentric. Another thing they share is their total disregard for Time. In these works, Time is neither a solid thing one must travel across nor a liquid passage flowing down some more elemental thing. In these stories, Time is not a thing with rules and causality at all. In fact, it’s not even a concept.

In a recent post about the Centennial Mountains in Idaho, I proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that Time does not exist in those hills. Through these three pieces of art, that list of Time-less places is extended.

Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream (1965)

Released on 1965’s Bringing it all Back Home, this track is, in my opinion, Bob Dylan at his near-best (his 23rd best song if you believe everything you read). At least it’s fast-paced and silly, which is often all I ask from art.

The stage is set quickly. The protagonist was riding on the Mayflower and he thought he spied some land. Timelines and realities are quickly distorted with the introduction of Captain Arab (a pseudo-Ahab from Moby Dick), who starts buying land with beads.

The second verse gets real wacky:

“I think I’ll call it America”

I said as we hit land

I took a deep breath

I fell down, I could not stand

Captain Arab he started

Writing up some deeds

He said, “Let’s set up a fort

And start buying the place with beads”

Just then this cop comes down the street

Crazy as a loon

He throw us all in jail

For carryin’ harpoons

As the song continues, we realize that Dylan is describing a world where Time does not flow as a river to some Eternal Ocean, but rather pools in the hollows of shore outcrops, as rich in activity and connectivity as any tidal pool at low tide. The various timelines of eastern North America all happen simultaneously.

After some six minutes of zany rollicks, the last verse brings us back home, with the introduction of Columbus, another European sailor who unleashed all manner of Christian Hell on this continent.

Well, the last I heard of Arab

He was stuck on a whale

That was married to the deputy

Sheriff of the jail

But the funniest thing was

When I was leavin’ the bay

I saw three ships a-sailin’

They were all heading my way

I asked the captain what his name was

And how come he didn’t drive a truck

He said his name was Columbus

I just said, “Good luck.”

Perhaps Dylan got the idea for this kind of twisted timeline from working on Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, which was written by the star of the next section, Rudy Wurlitzer. Or perhaps he had read Vollmann’s 1994 novel, The Rifles. Or perhaps Dylan, Wurlitzer, and Vollmann all sat down at some point in the past or future and drew up their outlines together, like any good writers’ group might.

Walker (1987)

This is a great picture written by one of my favorite writers, Rudy Wurlitzer. It portrays, in many ways, a story that takes place in liminal spaces.

Firstly, it takes place in that bizarre and dangerous time in American history between the successful implementation of Manifest Destiny (at least in the East-to-West sense) and the Civil War.

It is a threshold film in a second sense as well: it takes place on that murky line between Colonialism, where nations conquer other lands politically, and Neo-Colonialism, where nations use economic or cultural means to exert control.

Geographically as well, it takes place at a boundary, that is, on the Central American isthmus, which connects the two great land masses of the Americas.

Time in the film proceeds fairly normally at first. It is the tale of William Walker (Ed Harris), the soldier-of-fortune that Cornelius Vanderbilt (Peter Boyle) hired in 1855 to conquer and pacify Nicaragua in order that Mr. Vanderbilt could make his fortune in peace, unimpeded by the rights or well-being of the Nicaraguan land or people.

Walker is a bit unique among these three art-twins here for its systematic approach to anachronism. Rather than jumbling up time-lines like the big messy ball of frayed twine that Time is, Wurlitzer and Cox slowly introduce anachronistic elements, leading to a big weird bloody climax.

As the film progresses, Walker conquers Nicaragua by force and consolidates political power. As he does so, he descends into paranoia and just plain madness. He revokes his patron, Vanderbilt’s right to do business in the country and eats one of his soldier’s internal organs with a look of pure glee.

One of the first real tastes of anachronism comes about an hour into the film, just after Walker declares himself President of Nicaragua. Members of the opposition ride in a horse-drawn carriage, discussing what must be done. Two of the interlocutors read mo dern magazines, People and Newsweek, Walker adorning both covers. After their discussion about arming the peasants and anyone else who can help get rid of those gringos locos, a modern Mercedes-Benz (which is probably a reference to US-backed 20th Century Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle) cruises past the carriage, leaving the carriage in a cloud of dust and taking the viewer on to the next scene.

dern magazines, People and Newsweek, Walker adorning both covers. After their discussion about arming the peasants and anyone else who can help get rid of those gringos locos, a modern Mercedes-Benz (which is probably a reference to US-backed 20th Century Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle) cruises past the carriage, leaving the carriage in a cloud of dust and taking the viewer on to the next scene.

A few minutes later, as Walker walks along the shores of Lake Nicaragua, discussing Ends and Means, a reclining man nurses a Coca-Cola and smokes a Marlboro cigarette. These images are clear in their prophesying of the neocolonial assault of American companies and products that is, at the same time, going to come and come already to Central America.

The climax of the film comes as a coalition of Central American soldiers descends violently upon the main plaza of Granada. Walker orders the prisoners shot, and strides toward battle, singing Onward Christian Soldier, a nod to Christianity’s storied role in the subjugation of indigenous peoples. They come out into the carnage, and a helicopter descends into the plaza, releasing its spores of trigger-happy US soldiers, a cameraman, and a CIA man, all there to rescue anyone with a US passport from the carnage the US soldiers have created.

As Graham Fuller, in his essay Apocalypse When? about Walker, says:

This is not Saigon in 1975 but Granada, Nicaragua, in 1856, and the airlift is an anachronistic deus ex machina. Cox and the screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer conceived their film about William Walker… as a bloody comic opera cum parable to protest the Reagan administration’s support of the contra war against the democratically elected Sandinista government.

And so, how could time possible exist if the same story keeps happening in the same place, over and over (and over) again.

The theme of this film may be summed up best by Walker himself near the end of the film. He tells a group of battle weary Nicaraguans:

You all might think that there will be a day when America will leave Nicaragua alone. But I am here to tell you, flat out, that that day will never happen, because it is our destiny to be here. It is our destiny to control you people. So no matter how much you fight, no matter what you think, we’ll be back, time and time again.

Similar to what Grady tells Jack Torrence in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), the US has always attempted to control Nicaragua, so how could it ever be (or how could it ever have been) otherwise.

The Rifles (1994)

Of the three Time-twins I’ve brought up, William T. Vollmann’s novel is probably the least accessible. Mostly because you have to read it, rather than just watch or listen. Although there are some nice drawrings along the way, done by the author himself.

The structure of the book is something of a mixture of Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream and Walker. It is more systematic than Dylan, but includes much more interwoven anachronism than Walker.

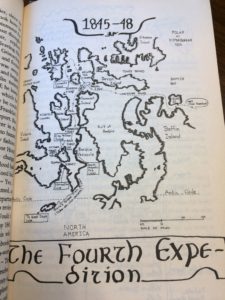

The main thrust of The Rifles’ narrative can be divided into two big patches of storylines. The first describes the four voyages of Sir John Franklin, a British explorer seeking the ever-sought-after Northwest Passage to China through Canada’s Polar Regions in the first half of the 19th Century. The second strand is a probably-mostly-true account of Vollmann’s own wanderings in northern Quebec and Nunavut in the early 1990s, including a terrifying account of his ill-prepared two-week stay at the magnetic North Pole.

Like Dylan’s Dream, this book contains some great adventures and some nice chuckles. What is truly interesting, though, is the way Vollmann collapses the hundreds of years between Franklin’s adventures and his own.

In fact, Vollmann (who has dubbed himself Captain Subzero for this rollick) reveals that he actually is John Franklin, and John Franklin just happens to be him, too, through reincarnation and its inverse. Throughout their respective adventures, time continuously eddies around them, causing them to overlap or drift apart, as the case may be.

This bizarre non-existence of Time in the far-north is proven irrevocably by Subzero and Franklin’s connection through an indigenous woman living in Inukjuak, Quebec . Her name is Reepah. Through his dry, often awkward romance with this Inuk woman, Subzero becomes the reincarnation (or grave-twin) of John Franklin, who had romanced the same woman about 150 years before.

I mean, at the same time, since there is no Time.

One described time-swirl occurs during Franklin’s Fourth Expedition. Upon landing in Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island, Sir John Franklin begins to wander through the dirty streets and, spying an air terminal, goes in to call his wife in London from a payphone. Neither payphones nor air terminals, of course, were in existence at the time of Sir John’s voyage from 1845 to 1848. But thanks to his connection with Subzero, this time-leap is not only possible, but inevitable.

Vollmann’s work is set apart from the other two grave-twins discussed here also because of the explicit discussion of the bizarre nature of time. Vollmann uses a third character, Sir James, from Sir John’s original timeline, at one point to draw attention to the caprices of Time:

On the one hand, there was the matter of Reepah – who existed, of course, only to the extent that Sir John was Subzero; and precisely to that extent Sir John was beyond Sir James’s ken – another sort of creature entirely, from another time! – but she existed nonetheless, and so his friend Sir John was not entirely Sir John anymore.

And later, as Sir John walks about the airport, thinking of Reepah, Vollmann (or Subzero, or Sir John) wonders:

Ask yourself: are you behaving differently at this very moment because someone not yet born for a century or more will someday think about you? You cannot prove the contrary. – What’s the difference anyway whether it’s so? Ice-floes, no matter how white, and water, no matter how blue or grey, eventually reach the same color in the distance.

And so the story goes, dipping in between futures and pasts. The only thing, perhaps, that remains constant, is the arrival and dangerous meddling of European explorers (which is a newer term for conqueror and older term for tourist, as it were).

How Many Times

If one were forced to extract a lesson from this type of art, the Time-less kind, it might be something like this Haudenosaunee teaching quoted in Winona LaDuke’s All Our Relations:

We are part of everything that is beneath us, above us, and around us. Our past is our present, our present is our future, and our future is seven generations past and present.

The three pieces of art I’ve talked about here share something like this worldview, one in which Time does not exist. Or at the very least, one in which we keep repeating the same pattern of things. All three deal with collisions between European conquerors and Native American populations, to some extent or another. In this context, the pattern of events that are repeated is one of violence, exploitation, and more of those same two ingredients, time and again.