In the last year, I spent a lot of time staring at two sets of things: maps of Idaho and Seven Dreams: A Book of North American Landscapes by William T. Vollmann.

Alex and I were planning the “exact” path that we would take on the Yell-to-Hell, a peak-bagging thru-hike in Idaho which we’ve discussed at some length in other posts. William T. Vollmann’s series of novels examines the encounters between European colonizing expeditions and Native North American civilizations.

In each of the Dreams, there is a preoccupation among the Europeans with filling the empty spaces on the map. The narratives portray the Europeans as a people beset by a deep anxiety relating to the unknown. The Terra Incognita, specifically, and the peoples who were familiar with what was, to them, unfamiliar.

Centuries or decades later, I am a European-American, though between 4 and 13 generations removed from the Europe famous on wall maps and World War II movies. I’ve lived my whole life in North America, visiting southern Europe, whose blood I have none of anyway, only once.

But I have found myself with a similar preoccupation with maps and the unknown.

Which side of whose map

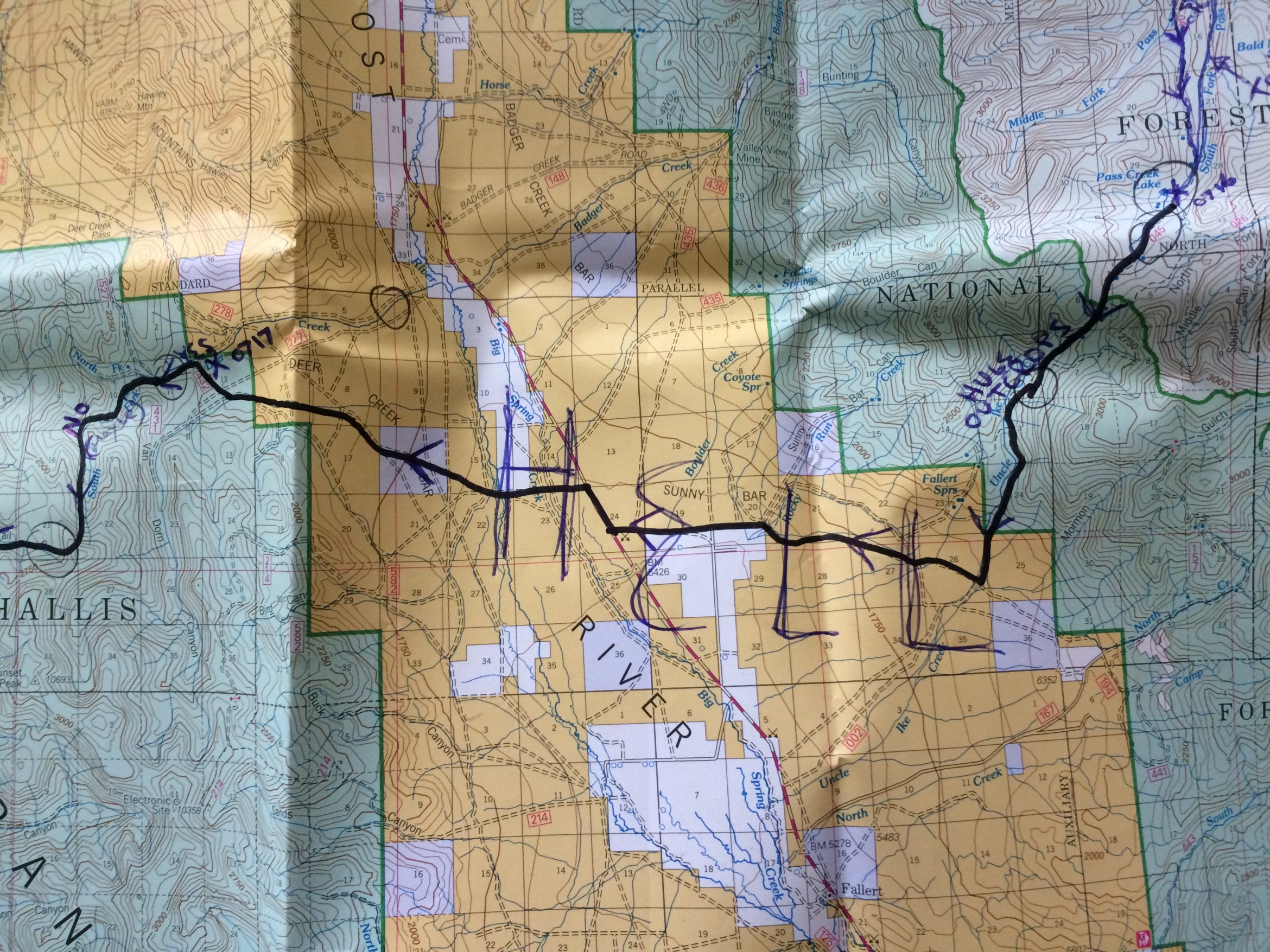

As I poured my attention over Idaho’s maps, I tried to imagine what the hills and valleys looked like. I tried extrapolating from the contour lines and blue gashes, which are somehow mountains and creeks. They are so exquisitely mapped on the United States Forest Service maps of the Salmon-Challis National Forest, the Caribou-Targhee National Forest, and the many others I looked over.

In making the plans for our East-to-West traverse of Idaho’s mountain ranges, we looked at names and contour lines that were unfamiliar not our own civilization, but only in our own experience.

I laboured under the illusion that I was occupying some sort of negative space from the European mappers and conquerors in Vollmann’s books. They fought a compulsion toward the unknown, as in the unmapped. I was fomenting a similar compulsion toward the unknown, as in the unseen-by-me.

In other words, they had a compulsion to see in order to map; Alex and I had a compulsion to see what we had stared at on maps.

Another thing I’ve been wrong about

After a couple hundred miles, with the map inside the territory, as it were, did I realize that we were engaged in the same mapping endeavor as our European forebears. We were slowly filling in their maps with maps of our own. Annotations, perceived corrections, names more appropriate to our experiences.

There was no negative space. There was no real difference, maybe, between ourselves as outdoor recreators seeking a deeper relationship with our homeland, and our ancestors who sought political authority and resource wealth.

I have spent time in conversation and in my head villainizing my own ancestors for their violence and thievery. To come to understand that I enthusiastically engage in those same basic activities, that I share their same basic drives, is unsettling.

That it is unsettling, though, is what makes it a topic worth mulling over.

Leave a Reply