On one particular night spent alone in a tent in the Idaho backcountry, I had a peculiar dream. I was in the basement of the house that I grew up in, in Idaho Falls, Idaho. In this dream, my siblings and I were supposed to be moving my grandmother out of the house, as if the house were hers. I was tasked with staying behind to meet the new owners, to hand over the keys and the care, as it were, of the whole operation.

As I waited for whomever was coming, I wandered around the basement where I had spent so great a portion of my formative years. In the cluttered storage room, now unencumbered by our marginal belongings, I noticed a door that I had never seen before. I opened it, and climbed the hidden staircase that had lain behind it, unclimbed for so many years. The staircase led to a large rooftop, overlooking a courtyard that did not belong to the house I knew. I strode down the stairs, which had become covered by a smattering of two-dollar bills, excited to find my older brother and tell him about the new part of our old house.

I woke up in this part of the dream. Or rather, I woke up in a tent, the nylon netting of which granted the moon a set of rainbow wings as it reached my eye, so many thousands of miles below it. During the next few days, spent trudging macabrely through the foothills of the Beaverhead Mountains, one possible meaning to the dream slowly revealed itself to me. I had spent almost 20 years at the beginning of my life in Eastern Idaho, and only after almost 10 years of living elsewhere in the world, only now was I finally getting to know the mountains that had served as a backdrop to my life. I was becoming aware of entirely new staircases, rooftops, and courtyards of a home that I thought I had known.

This experience of discovery within the realm of the known, even the realm of home, is an exquisite one. Either exquisitely painful, as when one has left childhood far enough behind to start being told the family secrets; or exquisitely joyful, as I was experiencing in my new exploration of the old outdoors.

In the last few months, I have enjoyed this same sense of acquiring a deeper connection to the land I live in through the art of James Castle. I stumbled upon his art in a recent visit to the Boise Art Museum. I was immediately taken by the deep range of grays in the vivid, realistic landscapes and the simple, mask-like human figures.

My investment and interest in this new artist reached a higher register of harmonic when I saw that he was an Idaho native. Even more so when I read the plaque describing the materials of one of his drawings, which read, “Soot and saliva on found paper.”

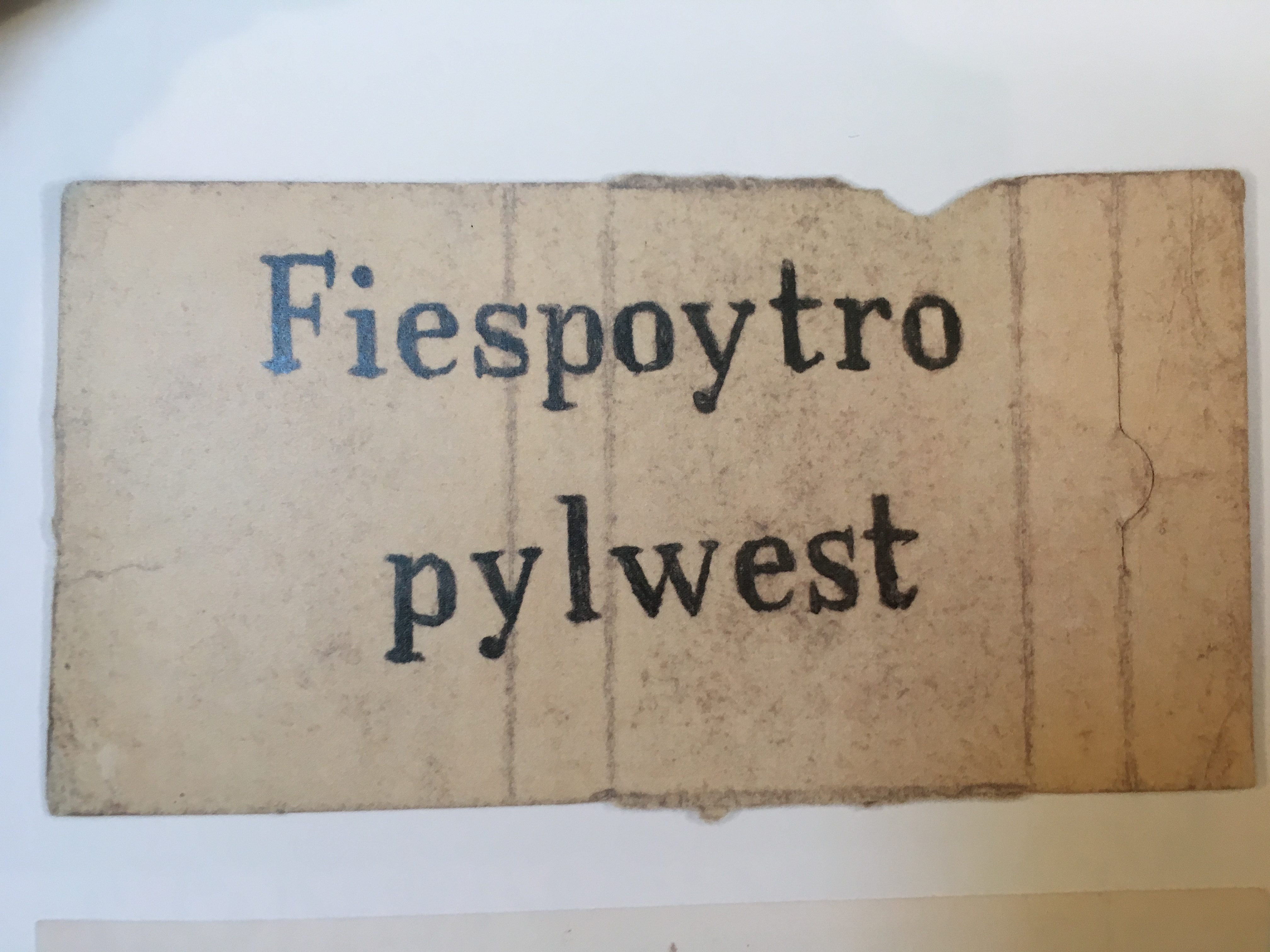

The more of Mr. Castle’s art I see, the less I feel I have to say about it, and the deeper I feel it in my bones and in the land around me. Even his simplest-seeming of drawings have a way of pulling me inside the rough, torn edges of whatever cardboard scrap he found and ritualized. His more surreal pieces have an even stronger pull for me. Particularly, his depiction of large, monolithic structures scattered about any given landscape. As if the trees shed their branches and leaves, revealing something more animistic and soul-like about whatever they are below what we see.

Other powerful images show houses deconstructed, existing no longer as single entities, but split into vertical spires, each section standing a few meters from its neighbor, which used to be just another part of itself. Another shows structures bereft of all but their roof. The roof having snuggled up to the ground below, a new pair, erasing, as it were, the space in which the masked and deformed people of Castle’s other drawings might have inhabited.

Besides the obvious reference to the dreamlike quality of Castle’s drawings, I believe that something deeper is present in his art. It seems to me that James Castle, in virtue of where and how he grew up, became a sort of unfiltered conduit of the Land. Having grown up deaf, fairly isolated on a small farm in Garden Valley at the turn of the century, unencumbered by language or linguistic communication, he was able to perceive and conceive of the land in ways that, while strange, may be closer to what the land actually is than how many of us experience it. Most the rest of us, blinded by our words and concepts, have to hope for the odd dream to reveal to us what James Castle managed to live in every day. Thankfully, he left us some postcards of his travels.

Leave a Reply